|

|

|

Archaeological Myth Bustingat Palomar Mountain's Nate Harrison SiteBy Seth Mallios Legends of Nate Harrison loom large in the historical lore of San Diego County. Mythical stories abound of the region's first African-American homesteader, this former slave from the South who lived during the late 19th and early 20th centuries atop Palomar Mountain. The tall tales have grown over time. Each subsequent generation has added to Harrison's larger-than-life status as mountain man, pioneer, and emancipated slave. Current popular myths maintain that he made his coffee strong by adding a lizard to the grinds, that he could tame even the wildest of horses, and that he escaped slavery on a raft down the Mississippi River, just like "Jim" in Mark Twain's 1884 classic Huckleberry Finn.

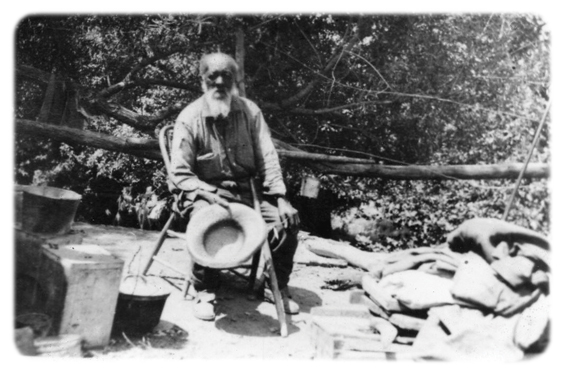

Pioneer Nate Harrison at his cabin on the west side of Palomar Mountain in the early 1900s Discerning fact from fiction regarding the details of Nate Harrison's life is no simple matter; even some of the most seemingly reliable sources present glaring historical contradictions. For example, the San Diego Union errantly reported in 1884 that Harrison had drowned, historical census records in 1880 separately listed his birth state as Kentucky and Alabama, and his birth year on various 19th-century voting records ranges from 1822 to 1835. Nonetheless, a majority of contemporary primary sources and maps suggest a somewhat reliable chronology for Harrison that includes his birth in the American South during the 1820s or '30s, his migration to California during the Gold Rush, and his eventual settlement atop Palomar Mountain during the second half of the 19th century. Harrison's final years are well chronicled, concluding with his death from natural causes at San Diego County Hospital on October 10, 1920.

Aerial photograph of San Diego State University student archaeologists excavating the foundation of the stone cabin in the summer of 2006 According to various 20th-century accounts, Nate Harrison was "Palomar's hermit" and had only "the comradeship of the wild things." The SDSU archaeological team has uncovered artifacts that suggest the presence of women and children at the site, including a cosmetic tin with white make-up, a toy tea cup, and two marbles. Furthermore, dozens of recently archived historical photographs from the early 1900s reveal that Harrison entertained numerous guests and was a tourist attraction for many early San Diegans. It is worth noting that there are more different contemporary historical photographs of Nate Harrison than any other 19th-century San Diegan. Harrison may have chosen to live by himself on Palomar Mountain, but he was neither isolated nor alone.

An early 20th-century photograph shows Nate Harrison at his patio, his primary work area, next to a stack of animal hides Overt ethnic epithets are commonplace in many of the historical accounts involving Nate Harrison; the road leading to his homestead was officially named "Nigger Nate Grade" until the NAACP successfully petitioned to have it changed in 1955. Less-obvious racial slurs and stereotypes also permeate Harrison's legend, including assertions that he was a lazy black man. Years after his passing, some writers claimed that he "never did a solid day's work" and that he "was absolutely allergic to labor of any kind." It is difficult to assess character traits archaeologically; individual historical artifacts rarely reveal something as specific as one's work ethic. However, the overall assemblage from the site has an overwhelming amount of sheep bones, multiple sheep shears, and two of the historical photographs show stacks of animal hides. Multiple lines of archaeological evidence suggest that Nate Harrison ran his own cottage industry at the site, raising sheep and processing wool, hides, and possibly meat on a regular basis.

Nate Harrison Cabin by Marjorie Reed, oil on canvas, 1952. Courtesy Valley Center History Museum Even though current San Diego lore often portrays Nate Harrison as alone, poor, and avoidant of work, extensive evidence from the Nate Harrison Historical Archaeology Project reveals that Harrison engaged many visitors, owned a variety of ornate goods, and participated in a multi-faceted sheep industry. Archaeology is especially well-suited at busting historical myths. Whereas written accounts are carefully crafted by authors who are often all too aware of their audience, archaeological artifacts are originally deposited in the ground with far less agenda, bias, and purpose. It is for this reason, that they reflect a more democratic history.

|

2011 - Volume 42MORE FROM THIS ISSUE San Diego's First Chinese Community Chicano Park & its Wondrous Murals Sleeping Porches & Suffragist Banners Most Endangered List of Historic Resources People In Preservation Winners Preservation Community

Recent Acquisitions

DOWNLOAD full magazine as pdf (11.3mb) |

Mailing - PO Box 80788 · San Diego CA 92138 | Offices - 3525 Seventh Avenue · San Diego CA 92103

|