|

Black Gold in San Diego?By Mike BryantAround the turn of the twentieth century, the automobile was beginning to take hold in this country. The search for oil and gas to run these newfangled contraptions was all the rage, and San Diego was not to be left out. Hundreds of oil wells were dug in San Diego County from Oceanside in the north to San Ysidro in the south, from Ocean Beach to East County, and all points in between. The fact that San Diego does not resemble Tulsa might be a clue as to the success of these ventures. You don't remember seeing that oil derrick the last time you drove through Mission Valley or Kearny Mesa? That's because most of the wells turned up dry. No Texas Tea here!

Certificate of purchase from La Costa Oil Co., with Temecula, Chula Vista, and San Diego and Imperial Valley stocks shown in foreground, courtesy Bryant Collection; inset Mission Valley, 1914, courtesy Mike Cunningham

The first drilling for oil in San Diego County took place in National City in the 1880's. The Bancroft Well, as it was named, struck water at 700 feet. At that time, water was worth more than oil or gas. The drilling was stopped. Water was as good as gold in arid San Diego. Everyone was happy with the find, and felt that there was no need to go any deeper. In fact, most drilling operations struck water, but a few did find oil and gas deposits. The problem was there weren't sufficient amounts of oil and gas to make it profitable, or the companies simply ran out of money to keep the operations going.

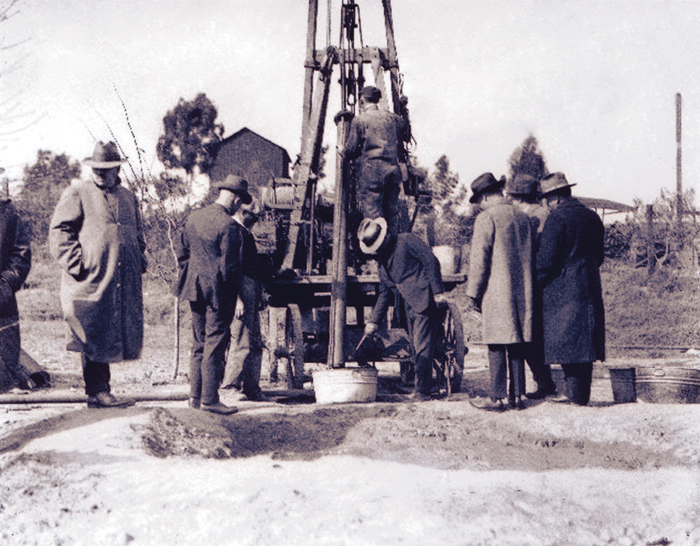

California has been a part of the oil rush since it began, this is San Diego's small role in the dependency we all share today. National City, 1924. Courtesy Mike Cunningham

The Mayor it seems was no stranger to controversy. Born July 16, 1865 in Iowa City, Iowa, Louis J. Wilde became an insurance salesman and made a small fortune investing in Texas oil. He moved to Los Angeles in 1902, but ended up in San Diego one year later. In San Diego, Wilde became a banker and started the American National and US National Banks. He financed the completion of the US Grant Hotel in 1910. On the hotel's opening night, October 15, 1910, Wilde presented to the people of San Diego a gift in the form of a $10,000 electric fountain across the street in Horton Plaza. The fountain, designed by noted architect Irving Gill, was the first successful combination of flowing water and lights. Wilde had it inscribed "Broadway Fountain For The People."

Using a tripod and timer, Felix Kallis takes his picture next to Community Well #5 in Tecolote Canyon in 1940, courtesy of Rurik Kallis

As a lad growing up in the Linda Vista section of San Diego in the 1950's and 60's, I spent a lot of my free time exploring Tecolote Canyon. Little did I know that the old pile of lumber, near where the golf course clubhouse now stands, was one of "His Honor's" last attempts at becoming San Diego's first oil baron. It was not until the mid-1960's when I read a column by Herbert Lockwood titled "The Skeleton's Closet," in the weekly newspaper, the Independent, that I would learn the significance of that pile of old wood. According to Mr. Lockwood, the well in Tecolote Canyon was called Community Well Number 5, after the first four turned out to be dusters. At 1,274 feet, Number 5 fared no better than the previous four, so it was abandoned, as were the hopes and dreams of the good citizens of San Diego. The wooden derrick stood for many years, but it too eventually ended up as nothing more than a pile of memories, as was San Diego's search for "Black Gold."

|

2009 - Volume 40, Issue 1MORE FROM THIS ISSUE 2009 People In Preservation Award Winners San Diego Trust & Savings Bank Building Preservation Community

Reflections

The Whaley House Porch Returns Borrego's future lies in its past DOWNLOAD full magazine as pdf (9.7mb) |

Mailing - PO Box 80788 · San Diego CA 92138 | Offices - 3525 Seventh Avenue · San Diego CA 92103

|