BUTTERFIELD, IN ASSOCIATION WITH MESSRS. WELLS & FARGO, was responsible for building and repairing roads and bridges, and set up 150 stage stations. The delivery of mail was the top priority on the Butterfield stages; however, they did carry passengers who could afford the $200 fare, about $3,000 today. The fare did not include meals, which cost an average of a dollar each three times a day. These mail lines were guaranteed to be rugged, but they got the mail through.

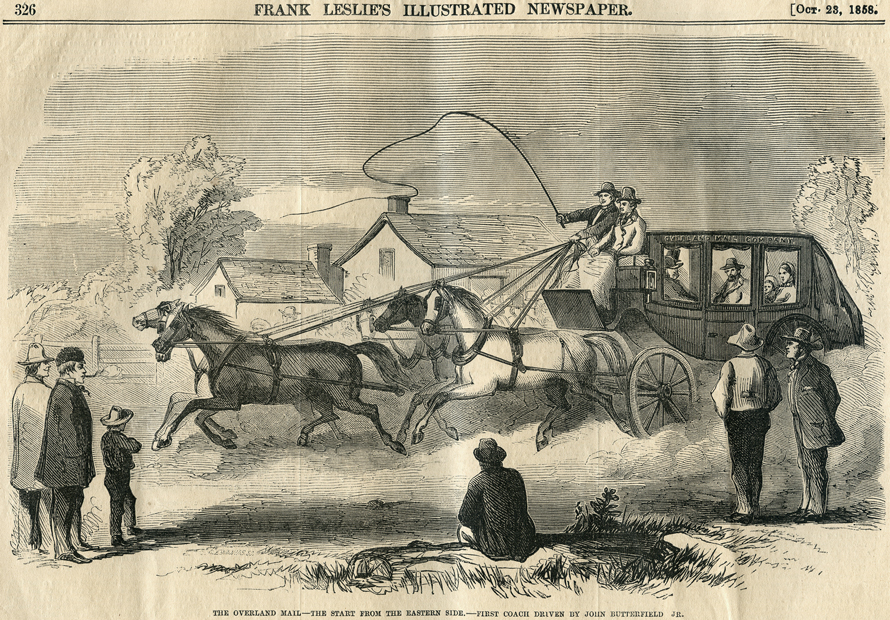

Stations were typically located 10 to 20 miles apart. There were no overnight stops, so passengers slept aboard the stage. They were allowed 25 pounds of baggage, two blankets, and a canteen. The time allotted for shifting the baggage and passengers was just nine minutes at a station. Then, the cry of "all aboard" and young John Butterfield's crack of the whip sent the stage flying again.

At each station, passengers disembarked for a quick meal and to refresh themselves while, at "swing stations," the driver changed the horses. Most stages made the journey from St. Louis to San Francisco in about 22 days.

The Butterfield Line used two types of coaches. The stage coaches we're familiar with—the famous Concord coaches, manufactured by Abbot, Downing and Company of Concord, New Hampshire—served the beginning and end of the line. Other, plainer vehicles called stage wagons, or celerity wagons, were the work horses used for much of the route. Concord coaches were full bodied coaches while the stage wagons had open upper sides and canvas tops over a frame.

|