|

From Whence We Came: The Eaton Fire

By Kathryn Fletcher

March/April 2025

|

Kathryn Fletcher's childhood home in Altadena survived the January 2025 Eaton fire. She initially heard that the Tudor Revival style house, built in 1925, was destroyed. Then the Los Angeles Times published a photo of it, damaged but still standing. |

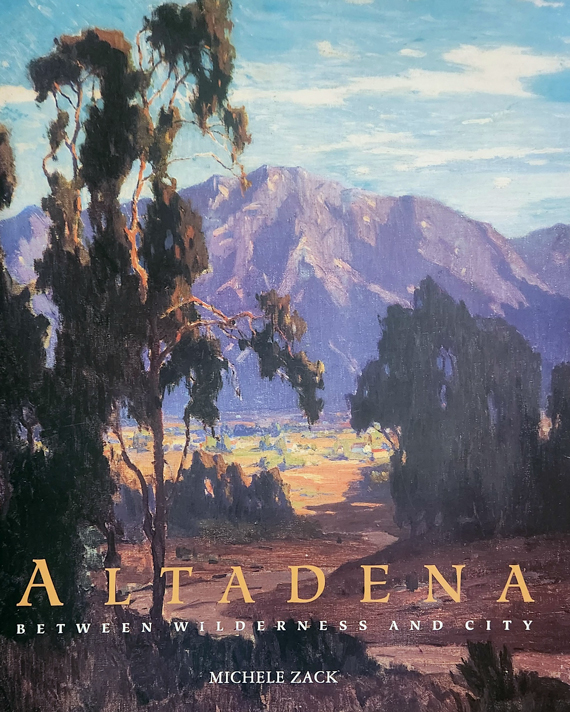

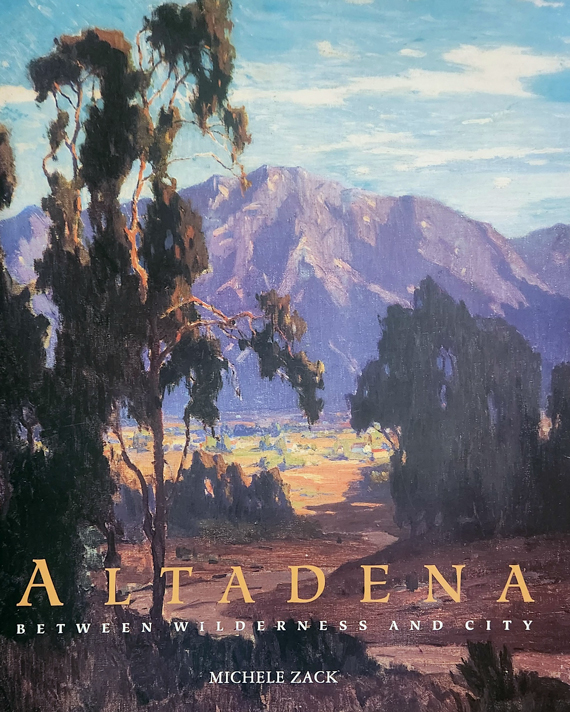

The Altadena Historical Society book prized by former resident Kathryn Fletcher |

Editor’s note: Kathryn is head docent and site manager at the Warner-Carrillo Ranch House Museum near Warner Springs

Nestled at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains below 5,700-foot Mount Wilson and above the city of Pasadena, unincorporated Altadena is no stranger to fires, floods, earthquakes, and Santa Ana winds. But the January 2025 Eaton Fire, which took 17 lives, destroyed an estimated 9,418 structures, and damaged over 1,000 more, marks an immeasurable loss—not just for its residents, but for those of us who were fortunate enough to be raised there. A diverse and culturally rich community, Altadena has long held a special place in the hearts of many.

It is my hometown, and that of my grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, and 14 cousins. Of the seven different homes my family built or bought and lived in, only three remain after the inferno—one of them, remarkably, is my childhood home on Boulder Road. Street after street of homes are gone. On our block alone, only three of twenty houses survived. My cousins’ home across the street and my grandparents’ house a block away both burned. For days, I believed my childhood home was lost too. Then a cousin sent me a Los Angeles Times article featuring the 100-year-old Tudor Revival style house, still standing, though damaged.

That moment—of believing that my home for 18 years was gone and then learning it had survived—was an emotional revelation. It underscored the power of place and the resilience not just of buildings, but of those who cherish them. Whether the current owners will stay and restore it remains uncertain; I know that recovering from such devastation will take years. Still, Altadenans are resilient.

Altadena’s loss is not just personal—it is historic. A community defined by its mix of architectural styles and cultural landmarks, it has now lost irreplaceable treasures dating back to the 1870s. The grandeur of Millionaire’s Row has dimmed with the destruction of Scripps Hall, the 1904 Arts and Crafts residence of William Armiger Scripps (grandfather of Ellen Browning Scripps), and the 1887 Queen Anne-style Andrew McNally House. Zane Grey’s Santa Fe-style home near Eaton Canyon, once a writer’s retreat, is no more. The Altadena Town and Country Club, where we learned swimming, golf, tennis, and ballet, and celebrated family weddings, is gone.

Yet, some landmarks were spared. The Gamble House on the Arroyo Seco, designed by Greene & Greene, still stands, as do the Woodbury-Story House, the Balian Mansion, and Christmas Tree Lane. Even the 1882 Mountain View Cemetery, where generations of families, including mine, are laid to rest, caught fire but survived. Farnsworth Park lost its beloved 1930s WPA-era William Davies Memorial Building and amphitheater; my elementary school and the library are also gone. Eliot Junior High, another stunning WPA project, suffered heavy damage, including the complete loss of its massive auditorium, where I, as a young student, learned that President Kennedy had been shot. My father was a member of Eliot’s first graduating class, one more reminder of my family’s deep ties to this place.

The devastation extended to places of worship as well. St. Elizabeth’s Church, a 1926 Walter Neff-designed masterpiece still stands, as does my former church across the street, Westminster Presbyterian, dedicated in 1928 with three rose windows by Judson Studios. But others were lost, including a century-old Jewish temple, one of the first buildings to burn. And of course, the beautiful mountains and hiking trails, once lush from two consecutive rainy seasons, are now barren and gray with ash.

Through it all, the Altadena Historical Society, founded in 1935 to “gather and preserve for posterity the early and authentic records of the community,” will play an essential role in recovery. I treasure my copy of Altadena: Between Wilderness and City by Michelle Zack. It reminds me that you can go home again, at least in your memories.

This tragic experience has deepened my understanding of why we fight so hard to preserve historic places. My current home is a Cliff May-inspired ranch house in Warner Springs that my grandparents built in 1948. For decades, four generations of my family shared it as a beloved retreat until the trustee of the estate insisted on its sale. I could not let it go. Almost twenty years ago, I left my career as a landscape designer in Newport Beach, exercised my right of first refusal, and became its steward. My grandparents had ensured that provision in their trust because they knew: Once a historic home is lost, it is lost forever.

The survival of my Altadena home, and my personal fight to keep my Warner Springs home, are two sides of the same story: one of resilience, stewardship, and the deep emotional connection we have to the places that shape us. This is why the work that SOHO and other preservation organizations do is so critical. Saving historic buildings is not just about architecture; it is about preserving the places that anchor us to our past, our identity, and our shared history. Whether through fire, time, or development pressures, these sites are always at risk. And yet, when they endure, they remind us that our histories—both personal and collective—are well worth preserving.

BACK to table of contents

|

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

|