|

Kumeyaay Land: Baja California's Endangered Rural Heritage

May/June 2018

By Maria E Curry

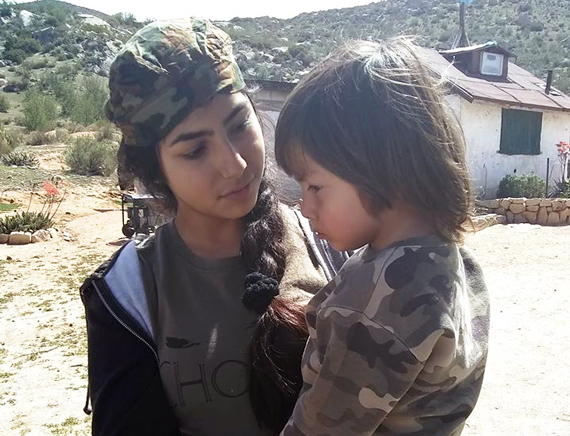

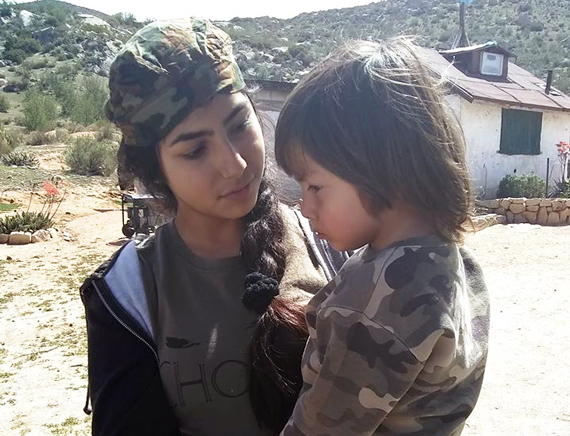

Araceli Leal, 12, holds her 3-year-old cousin, Joseph Leal. She speaks and sings in Kumeyaay. Photo by Maria Curry |

Cañon del Alamo, Valle de las Palmas, Tecate, B.C. Photo by Eduardo de la Peña

|

Abandoned adobe without roof, next to Sol de Media Noche Winery, Valle de Guadalupe, Ensenada, B.C. Photo by Maria Curry |

Group from Baja Camping, Cañon de los Alamos, with Kumeyaays Araceli Leal (fifth from left), Norma Meza (fourth from right), and her brother, Ruben Osuna (far right), Valle de Guadalupe, Ensenada, B.C. Photo by Eduardo de la Peña |

Norma Meza explaining to Ron Wilson the use of a plant as soap to wash clothes, Cañon del Alamo, Valle de las Palmas, Tecate, B.C. Photo by Maria Curry |

As Baja California experiences a boom in wine industry tourism, the rural area between Tecate and Ensenada is facing rapid development. This is bringing change to heritage landscapes and historic structures from the Kumeyaay culture (or Kumiai, as it is spelled in Mexico) in Valle de Guadalupe and Valle de las Palmas.

Popular wine tours and festivals in Valle de Guadalupe, a short drive inland from Ensenada, offer visits to lush wineries with beautiful modern or traditional architecture, wine tasting, and sales of cheese, olives, bread, and other local temptations. Few tourists are aware that historic ranches and remnants of adobe missions along the wine route are slowly disappearing for lack of maintenance and abandonment.

Close to Puerta del Cielo Winery in Ensenada are the ruins of the Dominican Mission, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (1834). The Russian Community Museum in an old adobe home commemorates the presence of Russian ranchers dating from 1905. Still more adobes are in need of stabilization and restoration.

In March, Eduardo de la Peña of Baja Camping organized a day trip at $20 per person to Cañon del Alamo in Valle de las Palmas to meet members of a Kumeyaay community. Kumeyaays settled in the region 12,000 years ago. They are now separated by an artificial border, with one group in Baja California and the other in California.

The Baja California communities include Juntas de Neji, Peña Blanca, Aguaje de la Tuna, Lázaro Cárdenas, Valle de las Palmas, El Hongo, San José de la Zorra, Necua, la Huerta, Rosario, and Santa Catarina. In San Diego County, Kumeyaays live in Manzanita, Campo, Jamul, Viejas, San Pasqual, and Santa Ysabel.

The Mexican Kumeyaay face far greater economic constraints than their relatively well-off U.S. counterparts. The native population in Tecate works and studies outside their community. Farming and cattle raising are no longer productive due to the scarcity of water; schools are absent from the community. This leads Kumeyaays to commute for everything to Valle de las Palmas and Tecate.

Kumeyaay land is known as ejidos, which combines communal ownership with individual use. Politicians in the past have attempted to seize Kumeyaay territory in Cañon del Alamo but the natives resisted, as they did when Spanish missions were established in the region. People still hunt rabbits and collect acorns, which they grind and cook, for nourishment.

Our group was invited into the area by Kumeyaays who have known Eduardo for over 25 years and consider him part of their family. We met with Norma Meza, a Kumeyaay who works as Promoter of Indigenous Affairs in Tecate's municipal government. Eduardo taught us to say "auka" (hello in Kumeyaay) out of respect for her culture.

Norma learned Spanish when she was 13 years old as a student in the adult school in Valle de las Palmas town. She said there are only 16 people fluent in their language and that those under age 40 do not speak it well. Norma taught a group of 30 children Kumeyaay for four years with government grants and this helped her 12-year-old granddaughter, Araceli Leal, to learn it.

Araceli and her cousin, 3-year-old Joseph Leal, joined us on a well-worn trail. Before we began walking, Araceli sang in Kumeyaay while we were blessed with smoke billowing from a smoldering sage plant. Julian Garcia, Norma's husband, and her brother, Ruben Osuna Meza, also guided us.

During our tour, we learned about Kumeyaay culture, history, and ethnobotany. Norma noted there are plants used to combat fatigue and diabetes, or to remove bad energies. She showed us one plant used as soap for washing clothes and another to build houses. Norma did not know the scientific names of these plants and recommended a book that describes 47 of them and their uses: Kumeyaay Ethnobotany: Shared Heritage of the Californias by Michael Wilken-Robertson (2017, available on Amazon).

We walked in Alamo Canyon, crossing streams, passing alamo trees, and traversing rocky ridges. At the end of the day, we stopped in Tecate for delicious tacos. I want to thank Norma Meza and Eduardo de la Peña for giving us the opportunity to learn first-hand about this important community.

|

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

|